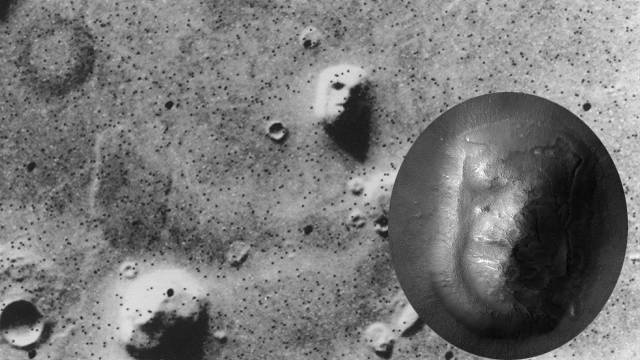

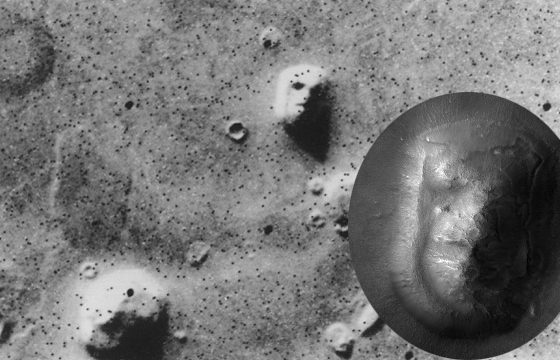

I have long quipped that, “humans are so good at seeing patterns that we find them where none exist.” But it wasn’t until sometime in graduate school that I learned the technical term for it: “apophenia.” (A visual apophenia is a pareidolia.) I still share this one with my students at some appropriate juncture almost every term.

Humans see figures in clouds, constellations in stars, the man in the moon, deeper significance in particular numbers (i.e., 3, 7, 12, 23, 666), and faces in geological formations. We are more prone to seeing relatively simple patterns in randomness than we are to missing simple patterns that do exist. We are also prone to asserting the reality of specific kinds of pattern: linearities, periodicities, and those that mimic some natural forms like the human face.

I contend that apophenia was adaptive. In fact, one of the key characteristics defining our shared experience is that humans are active, adaptive, meaning-makers. Our strength and our weakness is that we are so very good at identifying perceived patterns in all forms of stimuli: visual, aural, tactile, conceptual, cultural, social, and others. This is a characteristic humans share with all life, but we are particularly facile at it and this ability is one of the roots of our evolutionary success. It is also a source of many of our human problems.

Our ancestors who were more likely to discern patterns in the world were more likely to detect potentially harmful patterns, and so more likely to survive. They lived in the midst of nature, life was precarious, and mistakes could often be deadly. If they reacted to a potentially negative sensory pattern and it turned out to be false, then they could survive to laugh it off as an overreaction. But if they failed to notice those environmental signals, then the chances are one of those missed cues would eventually kill them.

Consider Og and Froosh, two early human ancestors hunting on the savannah. They grunt to one another in their proto-language…

Og: “Oh, look, there’s a rustling in the underbrush. Ya think it might be a sabertooth tiger?”

Froosh: “Nah, it’s just the wind.”

Og: “I dunno. I think I’m gettin’ outta here.”

Og runs away. Froosh, laughing at his timidity, is eaten by the sabertooth tiger that emerges from the brush. This may have happened many times before with Og running from shadows and the wind while Froosh mocked his jumpy friend. But the result was that, the one time Og was right, Froosh died. Cautious Og lives on to have a family and dies peacefully on his pallet at the ripe old age of 40. We learned, over many generations, that it is better to err on the side of apophenia.

There are only two ways we can be wrong: we can think we’ve detected a pattern when, in fact, there is none (Type I error, alpha error, or false positive), or we can miss detecting a pattern that really exists (Type II error, beta error, or false negative). Type I error happens when our detection gear is too sensitive, Type II error is a result of it not being sensitive enough.

The scientific method is inherently conservative — not in the political sense, but in the sense of requiring exceptional evidence for us to provisionally accept a newly identified pattern as probably real. It is designed to guard especially against those false positives. This is particularly important because humans are adapted to err on the side of Type I, and not Type II, error. All things being equal, we are far more likely to “see” something that does not exist than to not notice something that is real.

But being prone to Type I error is not now as adaptive as it long was. We have created an environment that no longer rewards this tendency as it did. We have created a world that is busier and chock full of signals, but many of those are not meaningful or relevant — and their speed and density is confusing, further encouraging us to find meaning where we can make it. We have also created a world where a greater proportion of the signals we experience are human created cultural products — reinforcing our default position of finding patterns (because they now really are everywhere), and so our likelihood of falling prey to apophenia (not everything is pattern).

Extreme cases of apophenia may be debilitating, and so usefully categorized as pathological, but such cases are rare. It’s everyday forms are far more common and often result in poor decisions. Apophenia is also doubtlessly related to human creativity, which is a necessary trait. Innovation entertains us, enriches us, and allows us to progress, individually and collectively. But too much creativity incorrectly applied leads us down blind alleys, wastes human effort, and even destroys lives.

As always, the trick is still to discern which patterns are real and which are (sometimes even well-meant) illusion. The trick is to find the balance allowing us to recognize the reality facing us and still see those possibilities not yet recognized. It is easy to recognize apophenia in those with whom we disagree. Our continuing challenge is to see it in ourselves, and in those we love and respect.

[I particularly recommend this Digital Bits Skeptic article for an in-depth exploration of apophenia.]

Kevin,

The following video at http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wS7CZIJVxFY for your consideration.